Geographical distribution of Russian speakers

This article details the geographical distribution of Russian-speakers. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the status of the Russian language often became a matter of controversy. Some Post-Soviet states adopted policies of derussification aimed at reversing former trends of Russification, while Belarus under Alexander Lukashenko and the Russian Federation under Vladimir Putin reintroduced Russification policies in the 1990s and 2000s, respectively.

After the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917, derussification occurred in the newly-independent Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and the Kars Oblast, the last of which became part of Turkey.

The new Soviet Union initially implemented a policy of Korenizatsiya, which was aimed partly at the reversal of the Tsarist Russification of the non-Russian areas of the country.[1] Vladimir Lenin and then Joseph Stalin mostly reversed the implementation of Korenizatsiya by the 1930s, not so much by changing the letter of the law, but by reducing its practical effects and by introducing de facto Russification. The Soviet system heavily promoted Russian as the "language of interethnic communication" and "language of world communism".

Eventually, in 1990, Russian became legally the official all-Union language of the Soviet Union, with constituent republics having the right to declare their own regional languages.[2][3]

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, about 25 million Russians (about a sixth of the former Soviet Russians) found themselves outside Russia and were about 10% of the population of the post-Soviet states other than Russia. Millions of them later became refugees from various interethnic conflicts.[4]

Statistics

[edit]

Native speakers

[edit]| Country | Speakers | Percentage | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 118,581,514 | 85.7% | 2010 | [5] | |

| 14,273,670 | 29.6% | 2001 | [6] | |

| 6,672,964 | 70.2% | 2009 | [6][note 1] | |

| 3,793,800 | 21.2% | 2017 | [7][note 2] | |

| 720,300 | 2.1% | 2021 | [8] | |

| 698,757 | 33.8% | 2011 | [6] | |

| 482,200 | 8.9% | 2009 | [9] | |

| 383,118 | 29.6% | 2011 | [6] | |

| 305,802 | 5.4% | 2016 | [10] | |

| 264,162 | 9.7% | 2014 | [11] | |

| 190,733 | 6.8% | 2021 | [6][12] | |

| 122,449 | 1.4% | 2009 | [6] | |

| 45,920 | 1.2% | 2014 | [6] | |

| 40,598 | 0.5% | 2012 | [6] | |

| 23,484 | 0.8% | 2011 | [6] | |

| 54,874 | 0.2% | 2022 | [13] | |

| 8,446 | 0.1% | 2001 | [6] | |

| 112,150 | 0.3% | 2011 | [6] | |

| 1,592 | 0.04% | 2011 | [6] | |

| 20,984 | 2.5% | 2011 | [6] | |

| 31,622 | 0.3% | 2011 | [6] | |

| 87,552 | 1.6% | 2021 | [14] | |

| 2,257,000 | 2.8% | 2010 | [15][note 3] | |

| 2,104 | 0.14% | 2009 | [6] | |

| 1,155,960 | 15% | 2011 | [16][note 4] | |

| 40 | 0.003% | 2011 | [6] | |

| 7,896 | 0.2% | 2006 | [6] | |

| 16,833 | 0.3% | 2012 | [6] | |

| 21,916 | 0.1% | 2011 | [6] | |

| 23,487 | 0.11% | 2011 | [17] | |

| 3,179 | 0.04% | 2011 | [6] | |

| 1,866 | 0.03% | 2001 | [6] | |

| 29,000 | 0.3% | 2012 | [18] | |

| 900,205 | 0.3% | 2016 | [19] |

Subnational territories

[edit]| Territory | Country | L1 speakers | Percentage | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harju County | 208,517 | 37.7% | 2011 | [20] | |

| Ida-Viru County | 121,680 | 81.6% | 2011 | [20] | |

| Riga Region | 326,478 | 55.8% | 2011 | [21] | |

| Pieriga Region | 87,769 | 25.9% | 2011 | [21] | |

| Vidzeme Region | 16,682 | 8.4% | 2011 | [21] | |

| Kurzeme Region | 47,213 | 19.3% | 2011 | [21] | |

| Zemgale Region | 54,761 | 23.3% | 2011 | [21] | |

| Latgale Region | 165,854 | 60.3% | 2011 | [21] | |

| Klaipėda County | 34,074 | 10.57% | 2021 | [12] | |

| Utena County | 18,551 | 14.54% | 2021 | [12] | |

| Vilnius County | 109,045 | 13.45% | 2021 | [12] |

Native and non-native speakers

[edit]Former Soviet Union

[edit]| Country | Speakers | Percentage | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,591,246 | 52.7% | 2011 | [22] | |

| 678,102 | 7.6% | 2009 | [23] | |

| 928,655 | 71.7% | 2011 | [24][note 5] | |

| 10,309,500 | 84.8% | 2009 | [25][note 6] | |

| 1,854,700 | 49.6% | 2009 | [9][note 7] | |

| 1,894,158 | 67.4% | 2021 | [12][note 8] | |

| 137,494,893 | 96.2% | 2010 | [6][note 9] | |

| 1,963,857 | 25.9% | 2010 | [26] | |

| 68% | 2006 | [27] |

Other countries

[edit]| Country | Percentage | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.24% native | 2012 | [28] | |

| 23% can have a conversation | 2012 | [29] | |

| 2.8% | |||

| 1.6% | 2011 | [30] | |

| 18% | 2012 | [31] |

Asia

[edit]Armenia

[edit]In Armenia, Russian has no official status but is recognized as a minority language under the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.[32] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 15,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 1 million active speakers.[33] 30% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 2% used it as the main language with family or friends or at work.[34] Russian is spoken by 1.4% of the population according to a 2009 estimate from the World Factbook.[35]

In 2010, in a significant pullback to derussification, Armenia voted to re-introduce Russian-medium schools.[36]

Azerbaijan

[edit]In Azerbaijan, Russian has no official status but is a lingua franca of the country.[32] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 250,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 2 million active speakers.[33] 26% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 5% used it as the main language with family or friends or at work.[34]

Research in 2005–2006 concluded that government officials did not consider Russian to be a threat to the strengthening role of the Azerbaijani language in independent Azerbaijan. Rather, Russian continued to have value given the proximity of Russia and strong economic and political ties. However, it was seen as self-evident that to be successful, citizens needed to be proficient in Azerbaijani.[37] The Russian language was co-official in the breakaway Armenian-populated Republic of Artsakh.

China

[edit]In the 1920s, the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese Nationalist Party sent influential figures to study abroad in the Soviet Union, including Deng Xiaoping and Chiang Ching-kuo, who both were classmates and fluent in Russian.[38] Now, Russian is only spoken by the small Russian communities in the northeastern Heilongjiang province and the northwestern Xinjiang province.[citation needed]

Israel

[edit]Russian is also spoken in Israel by at least 1,000,000 ethnic Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union, according to the 1999 census. The Israeli press and websites regularly publish material in Russian, and there are Russian newspapers, television stations, schools, and social media outlets based in the country.[39]

Kazakhstan

[edit]In Kazakhstan, Russian is not a state language, but according to Article 7 of the Constitution of Kazakhstan, its usage enjoys equal status to that of the Kazakh language in state and local administration.[32] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 4,200,000 native speakers of Russian in the country and 10 million active speakers.[33] 63% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 46% used it as the main language with family, friends or at work.[34] According to a 2001 estimate from the World Factbook, 95% of the population can speak Russian.[35] Large Russian-speaking communities still exist in northern Kazakhstan, and ethnic Russians comprise 25.6% of Kazakhstan's population.[40] The 2009 census reported that 10,309,500 people, or 84.8% of the population aged 15 and above, could read and write well in Russian and understand the spoken language.[41]

Kyrgyzstan

[edit]In Kyrgyzstan, Russian is an official language per Article 5 of the Constitution of Kyrgyzstan.[32] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 600,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 1.5 million active speakers.[33] 38% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 22% used it as the main language with family or friends or at work.[34]

The 2009 census states that 482,200 people speak Russian as a native language, including 419,000 ethnic Russians, and 63,200 from other ethnic groups, for a total of 8.99% of the population.[9] Additionally, 1,854,700 residents of Kyrgyzstan aged 15 and above fluently speak Russian as a second language, 49.6% of the population in that age group.[9]

Russian remains the dominant language of business and upper levels of government. Parliament sessions are only rarely conducted in Kyrgyz and mostly take place in Russian. In 2011, President Roza Otunbaeva controversially reopened the debate about Kyrgyz getting a more dominant position in the country.[42]

Tajikistan

[edit]In Tajikistan, Russian is the language of interethnic communication under the Constitution of Tajikistan.[32] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 90,000 native speakers of Russian in the country and 1 million active speakers.[33] 28% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 7% used it as the main language with family or friends or at work.[34] The World Factbook notes that Russian is widely used in government and business.[35]

After independence, Tajik was declared the sole state language, and until 2009, Russian was designated the "language for interethnic communication". The 2009 law stated that all official papers and education in the country should be conducted only in the Tajik language. However, the law also stated that all minority ethnic groups in the country have the right to choose the language in which they want their children to be educated.[43]

Turkmenistan

[edit]Russian lost its status as the official lingua franca of Turkmenistan in 1996.[32] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 150,000 native speakers of Russian in the country and 100,000 active speakers.[33] Russian is spoken by 12% of the population, according to an undated estimate from the World Factbook.[35]

Russian television channels have mostly been shut down in Turkmenistan, and many Russian-language schools were closed down.[44]

Uzbekistan

[edit]In Uzbekistan, Russian has no official status but is a lingua franca and a de-facto language throughout the country.[32] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 1,200,000 native speakers of Russian in the country and 5 million active speakers.[33] Russian is spoken by 14.2% of the population, according to an undated estimate from the World Factbook.[35] Throughout the country, there are still signs with Uzbek and Russian.

After the independence of Uzbekistan in 1991, Uzbek culture underwent the three trends of derussification, the creation of an Uzbek national identity, and westernization. The state has primarily promoted those trends through the educational system, which is particularly effective because nearly half the Uzbek population is of school age or younger.[45]

Since the Uzbek language became official and privileged in hiring and firing, there has been a brain drain of ethnic Russians in Uzbekistan. The displacement of the Russian-speaking population from the industrial sphere, science and education has weakened those spheres. As a result of emigration, participation in Russian cultural centers like the State Academy Bolshoi Theatre in Uzbekistan has seriously declined.[45]

In the capital, Tashkent, statues of the leaders of the Russian Revolution were taken down and replaced with local heroes like Timur, and urban street names in the Russian style were Uzbekified. In 1995, Uzbekistan ordered the Uzbek alphabet changed from a Russian-based Cyrillic script to a modified Latin alphabet, and in 1997, Uzbek became the sole language of state administration.[45]

Rest of Asia

[edit]In 2005, Russian was the most widely taught foreign language in Mongolia,[46] and is compulsory in Year 7 onward as a second foreign language in 2006.[47]

Russian is also spoken as a second language by a small number of people in Afghanistan.[48]

Oceania

[edit]Australia

[edit]Australian cities Melbourne and Sydney have Russian-speaking populations, most of which live in the southeast of Melbourne, particularly the suburbs of Carnegie and Caulfield. Two-thirds of them are actually Russian-speaking descendants of Germans, Greeks, Jews, Azerbaijanis, Armenians or Ukrainians, who either were repatriated after the Soviet Union collapsed or are just looking for temporary employment.[citation needed]

Europe

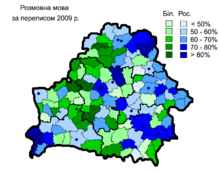

[edit]Belarus

[edit]

In Belarus, Russian is co-official alongside Belarusian per the Constitution of Belarus.[32] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 3,243,000 native speakers of Russian in the country and 8 million active speakers;[33] 77% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 67% used it as the main language with family or friends or at work.[34]

Initially, when Belarus became independent in 1991 and the Belarusian language became the only state language, some derussification started.[citation needed] However, after Alexander Lukashenko became president, a referendum held in 1995, which was considered fraudulent by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, included a question about the status of Russian. It was made a state language, along with Belarusian.[citation needed]

In most spheres, the Russian language is by far the dominant one. In fact, almost all government information and websites are in Russian only.[citation needed]

Bulgaria

[edit]Bulgaria has the largest proportion of Russian-speakers among European countries that were not part of the Soviet Union.[29] According to a 2012 Eurobarometer survey, 19% of the population understands Russian well enough to follow the news, television, or radio.[29] Native Russian speakers are 0.24%.[28]

Estonia

[edit]

In Estonia, Russian is officially considered a foreign language.[32] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 470,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 500,000 active speakers,[33] 35% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 25% used it as the main language with family or friends or at work.[34] Russian is spoken by 29.6% of the population, according to a 2011 estimate from the World Factbook.[35]

Ethnic Russians are 25.5% of the country's current population[49] and 58.6% of the native Estonian population is also able to speak Russian.[50] In all, 67.8% of Estonia's population could speak Russian.[50] The command of Russian, however, is rapidly decreasing among younger Estonians and is primarily being replaced by the command of English. For example, 53% of ethnic Estonians between 15 and 19 claimed to speak some Russian in 2000, but among the 10- to 14-year-old group, command of Russian had fallen to 19%, about one third the percentage of those who claim to command English in the same age group.[50]

In 2007, Amnesty International harshly criticized what it termed Estonia's "harassment" of Russian-speakers.[51] In 2010, the language inspectorate stepped up inspections at workplaces to ensure that state employees spoke Estonian at an acceptable level. That included inspections of teachers at Russian-medium schools.[52] Amnesty International continues to criticize Estonian policies: "Non-Estonian speakers, mainly from the Russian-speaking minority, were denied employment due to official language requirements for various professions in the private sector and almost all professions in the public sector. Most did not have access to affordable language training that would enable them to qualify for employment."[53]

The percentage of Russian speakers in Estonia is still declining, but not as fast as in the most of ex-Soviet countries. After overcoming the consequences of 2007 economic crisis, the tendency of emigration of Russian speakers has almost stopped, unlike in Latvia or in Lithuania.[citation needed]

Finland

[edit]Russian is spoken by about 1.4% of the population of Finland, according to a 2014 estimate from the World Factbook.[35] Making Russian language one of the most-spoken immigrant language in Finland.[54]

Until 2022 the popularity of Russian language was growing because of an increase in trade with and tourism from the Russia and other Russian-speaking countries and regions.[55] However after the year of 2022, various statistics show a notable decline in the popularity of Russian language in Finnish society. There was steadily-increasing demand for the knowledge of Russian in the workplace, which was also reflected in its growing presence in the Finnish education system, including higher education.[56] In Eastern Finland, most prominently in its border towns, Russian has already begun to rival Swedish as the second most important foreign language due to high tourism rate from Russia throughout the past decades.[57]

Georgia

[edit]In Georgia, Russian has no official status but is recognized as a minority language under the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.[32] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 130,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 1.7 million active speakers.[33] 27% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 1% used it as the main language with family, friends or at work.[34] Russian is the language of 9% of the population according to the World Factbook.[58] Ethnologue cites Russian as the country's de facto working language.[59]

Georgianization has been pursued with most official and private signs only in the Georgian language, with English being the favored foreign language. Exceptions are older signs remaining from Soviet times, which are generally bilingual Georgian and Russian. Private signs and advertising in the Samtskhe-Javakheti region, which has a majority Armenian population, are generally in Russian only or Georgian and Russian.[citation needed] In the Kvemo Kartli borderline region, which has a majority ethnic Azerbaijani population, signs and advertising are often in Russian only, in Georgian and Azerbaijani, or Georgian and Russian. Derussification has not been pursued in the areas outside Georgian government control: Abkhazia and South Ossetia.[citation needed]

The Russian language is co-official in the breakaway republics of Abkhazia,[60] and South Ossetia.[61]

Germany

[edit]Germany has the highest Russian-speaking population outside the former Soviet Union, with approximately 3 million people.[62] They are split into three groups, from largest to smallest: Russian-speaking ethnic Germans (Aussiedler), ethnic Russians, and Jews.[citation needed]

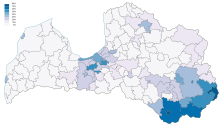

Latvia

[edit]

The 1922 Constitution of Latvia, restored in 1990, enacted Latvian as the sole official language.[63]

Despite large Russian-speaking minorities in Latvia (26.9% ethnic Russians, 2011),[64] the Russian language has no official status.[32] According to Russian sources, 55% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 26% used it as the main language with family or friends or at work.[34][better source needed]

A constitutional referendum, held in February 2012, proposed amendments to the constitution of Latvia to make Russian the second state language of Latvia, but 821,722 (75%) of the voters voted against and 273,347 (25%) for. There has been criticism that about 290,000 of the 557,119 (2011) ethnic Russians in Latvia are non-citizens and do not have the right to vote.[65] Since 2019, instruction in Russian is gradually discontinued in private colleges and universities, as well general instruction in public high schools[66] except for subjects related to culture and history of the Russian minority, such as Russian language and literature classes.[67]

Lithuania

[edit]In 1992 Constitution of Lithuania, the Lithuanian language was declared as the sole state language.[68] This was also the case in the 1922—1938 interwar constitutions.[69]

In Lithuania, Russian has no official or any other legal status, but the use of the language has some presence in certain areas. A large part of the population (63% as of 2011), especially the older generations, can speak Russian as a foreign language.[70] Only 3% used it as the main language with family or friends or at work, though.[34] English has replaced Russian as lingua franca in Lithuania and around 80% of young people speak English as the first foreign language.[71] Russian is still available to take in some schools in Lithuania, but is not mandatory like during the Soviet period. They have options to take German, French, Spanish, etc.[citation needed] In contrast to the other two Baltic states, Lithuania has a relatively small Russian-speaking minority (5.0% as of 2008).[68]

Unlike Latvia or Estonia, Lithuania has never implemented the practice of regarding some former Soviet citizens as non-citizens.

Moldova

[edit]In Moldova, Russian has a status similar to the other recognized minority languages;[72] it was also considered to be the language of interethnic communication under a Soviet-era law.[32]

According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 450,000 native speakers of Russian in the country and 1.9 million active speakers.[33] 50% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 19% used it as the main language with family or friends or at work.[34] According to the 2014 census, Russian is the native language of 9.68% of Moldovans, and the language of first use for 14.49% of the population.[citation needed]

Russian has a co-official status alongside Romanian in the autonomies of Gagauzia and Transnistria.[citation needed]

Romania

[edit]According to the 2011 Romanian census, there are 23,487 Russian-speaking Lipovans practicizing the Lipovan Orthodox Old-Rite Church. They are concentrated in Dobruja, mainly in the Tulcea County but also in the Constanța County. Outside Dobruja, the Lipovans of Romania live mostly in the Suceava County and in the cities of Iași, Brăila and Bucharest.[17]

Russia

[edit]According to the census of 2010 in Russia, Russian skills were indicated by 138 million people (99.4% population), and according to the 2002 census, the number was 142.6 million people (99.2% population). Among urban residents, 101 million people (99.8%) had Russian language skills, and in rural areas, the number was 37 million people (98.7%).[73] The number of native Russian-speakers in 2010 was 118.6 million (85.7%),[citation needed] a bit higher than the number of ethnic Russians (111 million, or 80.9%).[citation needed]

Russian is the official language of Russia but shares the official status at regional level with other languages in the numerous ethnic autonomies within Russia, such as Chuvashia, Bashkortostan, Tatarstan, and Yakutia, and 94% of school students in Russia receive their education primarily in Russian.[74]

In Dagestan, Chechnya, and Ingushetia, derussification is understood not so much directly as the disappearance of Russian language and culture but rather by the exodus of Russian-speaking people themselves, which intensified after the First and the Second Chechen Wars and Islamization; by 2010, it had reached a critical point. The displacement of the Russian-speaking population from industry, science and education has weakened those spheres.[75]

In the Republic of Karelia, it was announced in 2007 that the Karelian language would be used at national events,[76] but Russian is still the only official language (Karelian is one of several "national" languages), and virtually all business and education is conducted in Russian. In 2010, less than 8% of the republic's population was ethnic Karelian.

Russification is reported to be continuing in Mari El.[77]

Ukraine

[edit]

In Ukraine, Russian is seen as a minority language under the 1996 Constitution of Ukraine. According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 14,400,000 native speakers of Russian in the country and 29 million active speakers;[33] 65% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 38% used it as the main language with family or friends or at work.[34]

In 1990, Russian became legally the official all-Union language of the Soviet Union, with constituent republics having rights to declare their own official languages.[2][3] In 1989, the Ukrainian SSR government adopted Ukrainian as its official language, which was affirmed after the fall of the Soviet Union as the only official state language of the newly-independent Ukraine. The educational system was transformed over the first decade of independence from a system that was overwhelmingly Russian to one in which over 75% of tuition was in Ukrainian. The government has also mandated a progressively increased role for Ukrainian in the media and commerce.[citation needed]

In 2012 poll by RATING, 50% of respondents consider Ukrainian their native language, 29% - Russian, 20% consider both Ukrainian and Russian their mother tongue, another 1% considers a different language their native language.[78]). However, the transition lacked most of the controversies that surrounded the derussification in several of the other former Soviet Republics.[citation needed]

In some cases, the abrupt changing of the language of instruction in institutions of secondary and higher education led to charges of assimilation, which were raised mostly by Russian-speakers.[citation needed] In various elections, the adoption of Russian as an official language was an election promise by one of the main candidates (Leonid Kuchma in 1994, Viktor Yanukovych in 2004, and the Party of Regions in 2012).[79][80][81][82] After the introduction of the 2012 legislation on languages in Ukraine, Russian was declared a "regional language" in several southern and eastern parts of Ukraine.[83] On 28 February 2018, the Constitutional Court of Ukraine ruled that legislation to be unconstitutional.[84]

A poll conducted in March 2022 by RATING found that 83% of Ukrainians believe that Ukrainian should be the only state language of Ukraine. This opinion dominates in all macro-regions, age and language groups. On the other hand, before the war, almost a quarter of Ukrainians were in favour of granting Russian the status of the state language, while today only 7% support it. In peacetime, Russian was traditionally supported by residents of the south and east. But even in these regions, only a third of them were in favour, and after Russia's full-scale invasion, their number dropped by almost half.[85]

According to the survey carried out by RATING on 16-20 August 2023, almost 60% of the polled usually speak Ukrainian at home, about 30% – Ukrainian and Russian, only 9% – Russian. Since March 2022, the use of Russian in everyday life has been noticeably decreasing. For 82 per cent of respondents, Ukrainian is their mother tongue, and for 16 per cent, Russian is their mother tongue. IDPs and refugees living abroad are more likely to use both languages for communication or speak Russian. Nevertheless, more than 70 per cent of IDPs and refugees consider Ukrainian to be their native language.[86]

Rest of Europe

[edit]

In the 20th century, Russian was a mandatory language taught in the schools of the members of the old Warsaw Pact and in other communist countries that used to be Soviet satellites, including Poland, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Albania, the former East Germany and Cuba. However, younger generations are usually not fluent in it because Russian is no longer mandatory in schools. According to the Eurobarometer 2005 survey,[87] fluency in Russian remains fairly high, however, at (20–40%) in some countries, particularly those whose people speak a Slavic language and so have an edge in learning Russian (Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Bulgaria).[citation needed]

Significant Russian-speaking groups also exist in other parts of Europe[citation needed] and have been fed by several waves of immigrants since the beginning of the 20th century, each with its own flavor of language. The United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, Belgium, Greece, Norway, and Austria have significant Russian-speaking communities.[citation needed]

According to the 2011 census of Ireland, there were 21,639 people using Russian at home. However, only 13% were Russian nationals. 20% held Irish citizenship, while 27% and 14% were Latvian and Lithuanian citizens respectively.[88]

There were 20,984 Russian-speakers in Cyprus according to the 2011 census of 2011 and accounted for 2.5% of the population.[89]

Russian is spoken by 1.6% of the people of Hungary according to a 2011 estimate from the World Factbook.[35]

Americas

[edit]The language was first introduced in North America when Russian explorers voyaged into Alaska and claimed it for Russia in the 1700s. Although most Russian colonists left after the United States bought the land in 1867, a handful stayed and have preserved the Russian language in the region although only a few elderly speakers of their unique dialect are left.[90] In Nikolaevsk, Russian is more spoken than English. Sizable Russian-speaking communities also exist in North America, especially in large urban centers of the US and Canada, such as New York City, Philadelphia, Boston, Los Angeles, Nashville, San Francisco, Seattle, Spokane, Toronto, Calgary, Baltimore, Miami, Chicago, Denver and Cleveland. In a number of locations, they issue their own newspapers, and live in ethnic enclaves (especially the generation of immigrants who started arriving in the early 1960s). Only about 25% of them are ethnic Russians, however. Before the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the overwhelming majority of Russophones in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn in New York City were Russian-speaking Jews. Afterward, the influx from the countries of the former Soviet Union changed the statistics somewhat, with ethnic Russians and Ukrainians immigrating along with some more Russian Jews and Central Asians. According to the United States Census, in 2007 Russian was the primary language spoken in the homes of over 850,000 individuals living in the United States.[91]

Russian was the most popular language in Cuba in the second half of the 20th century. Besides being taught at universities and schools, there were also educational programs on the radio and TV. It is now making a come-back in the country.[92]

See also

[edit]- Russian world

- Russian diaspora

- Dialect continuum

- List of link languages

- Geolinguistics

- Language geography

Notes

[edit]- ^ Data note: "Data refer to mother tongue, defined as the language usually spoken in the individual's home in his or her early childhood." (From the Footnotes section in the cited source)

- ^ Based on a 2016 population of 17,855,000 (UN Statistics Division Archived 2014-01-25 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Population data by Eurostat, using the source year. "The number of persons having their usual residence in a country on 1 January of the respective year". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2018-11-08.

- ^ Based on a 2011 population of 7,706,400 (Central Bureau of Statistics of Israel[permanent dead link])

- ^ Includes 383,118 native and 545,537 non-native speakers.

- ^ People aged 15 and above who can read and write Russian well.

- ^ Data refers to the resident population aged 15 years and over.

- ^ Includes 190,733 native and 1,703,425 non-native speakers.

- ^ Data note: "Including all of persons who stated each language spoken, whether as their only language or as one of several languages. Where a person reported more than one language spoken, they have been counted in each applicable group."

References

[edit]- ^ ""EMPIRE, NATIONALITIES, AND THE COLLAPSE OF THE USSR", VESTNIK, THE JOURNAL OF RUSSIAN AND ASIAN STUDIES, May 8, 2007". Archived from the original on November 3, 2012.

- ^ a b Grenoble, L. A. (2003-07-31). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Springer. ISBN 9781402012983. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ a b "СССР. ЗАКОН СССР ОТ 24.04.1990 О ЯЗЫКАХ НАРОДОВ СССР". Archived from the original on 2016-05-08. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Efron, Sonni (8 June 1993). "Case Study: Russians: Becoming Strangers in Their Homeland: Millions of Russians are now unwanted minorities in newly independent states, an explosive situation". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ "Население наиболее многочисленных национальностей по родному языку". gks.ru. Archived from the original on 2018-03-20. Retrieved 2018-10-28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "Population by language, sex and urban/rural residence". UNdata. Archived from the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ Zubacheva, Ksenia (16 May 2017). "Why Russian is still spoken in the former Soviet republics". Russia Beyond The Headlines. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ "Опубликованы данные об этническом составе населения Узбекистана". Газета.uz. August 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Population And Housing Census Of The Kyrgyz Republic Of 2009" (PDF). UN Stats. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ "Russian language in decline as post-Soviet states reject it". Financial Times. 13 April 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ "Structure of population by mother tongue, in territorial aspect in 2014". Statistica.md. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Population and Housing Census 2021". Statistics Lithuania. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Language spoken at home | Australia | Community profile". profile.id.com.au.

- ^ "Language according to age and sex by region, 1990-2021". Statistics Finland. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Berlin, Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) (2011-11-09). "KAT38 Occupation, Profession". Adult Education Survey (AES 2010 - Germany). GESIS Data Archive. doi:10.4232/1.10825. Archived from the original on 2018-11-09. Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- ^ Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. "Selected Data from the 2011 Social Survey on Mastery of the Hebrew Language and Usage of Languages (Hebrew Only)". Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ a b Constantin, Marin (2014). "The ethno-cultural belongingness of Aromanians, Vlachs, Catholics, and Lipovans/Old Believers in Romania and Bulgaria (1990–2012)" (PDF). Revista Română de Sociologie. 25 (3–4). Bucharest: 255–285.

- ^ "Här är 20 största språken i Sverige". Språktidningen (in Swedish). 28 March 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ "Language Spoken at Home by Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over". American FactFinder, factfinder.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau, 2012-2016 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. 2017. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ a b "RL0433: Population by mother tongue, sex, age group and administrative unit, 31 December 2011". Statistics Estonia. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "TSG11-071. Ethnicities of resident population in statistical regions, cities under state jurisdiction and counties by language mostly spoken at home; on 1 March 2011". Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ "Population (urban, rural) by Ethnicity, Sex and Fluency in Other Language" (PDF). ArmStat. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ "Distribution of population by native language and freely command of languages (based on 2009 population census)". State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan. Archived from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ "PC0444: Population By Mother Tongue, Command Of Foreign Languages, Sex, Age Group And County, 31 December 2011". Stat.ee. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ "Results of the 2009 National population census of the Republic of Kazakhstan" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 November 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ "Национальный состав и владение языками, гражданство населения Республики Таджикистан" (PDF). Агентство по статистике при Президенте Республики Таджикистан. p. 58. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ "Украинцы лучше владеют русским языком, чем украинским: соцопрос". ИА REGNUM.

- ^ a b Население, Демографски и социални характеристики (in Bulgarian) (Том 1: Население ed.). Bulgaria: National Statistical Institute. 2012. pp. 33–34, 190.

- ^ a b c "Eurobarometer 386" (PDF). European Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ "Központi Statisztikai Hivatal". www.ksh.hu.

- ^ "Europeans and their languages". Publications Office of the EU. 20 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Русский язык в новых независимых государствах" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-10-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Падение статуса русского языка на постсоветском пространстве". Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 2016-10-25. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Русскоязычие распространено не только там, где живут русские". Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 2016-10-23. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Languages". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 13 May 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ ""Armenia introduces Russian-language education", Russkiy Mir, Dec, 10, 2010". Archived from the original on May 25, 2013.

- ^ "Biweekly". biweekly.ada.edu.az. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ^ 王先金 (2010). "Chapter 3: 蒋经国主政台湾, under subheading "邓小平与蒋经国是同学"". 孤岛落日: 蒋介石与民国大佬的黄昏岁月. 团结出版社. The relevant paragraph is included as an excerpt in "蒋经国曾把邓小平当大哥 称"吃苏联的饭"". 新浪历史——reprinted from 人民网. 2013-10-14.

- ^ "Russians in Israel".

- ^ "Population Grows to 15.4 Million, More Births, Less Emigration Are Reasons". Kazakhstan News Bulletin - Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan. 20 April 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ^ "Results Of The 2009 National Population Census Of The Republic Of Kazakhstan" (PDF). Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ "Language A Sensitive Issue In Kyrgyzstan". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 27 June 2011. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ "Tajikistan Drops Russian As Official Language". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ "In Post-Soviet Central Asia, Russian Takes A Backseat". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012.

- ^ a b c Dollerup, Cay. "Language and Culture in Transition in Uzbekistan". In Atabaki, Touraj; O'Kane, John (eds.). Post-Soviet Central Asia. Tauris Academic Studies. pp. 144–147.

- ^ Brooke, James (February 15, 2005). "For Mongolians, E Is for English, F Is for Future". The New York Times. New York Times. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ^ Русский язык в Монголии стал обязательным [Russian language has become compulsory in Mongolia] (in Russian). New Region. 21 September 2006. Archived from the original on 2008-10-09. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

- ^ Awde and Sarwan, 2003

- ^ "Diagram". Pub.stat.ee. Archived from the original on 2012-12-22. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ a b c "Population census of Estonia 2000. Population by mother tongue, command of foreign languages and citizenship". Statistics Estonia. Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ^ ""ESTONIA: LANGUAGE POLICE GETS MORE POWERS TO HARASS", 27 February 2007, Amnesty International". 27 February 2007. Archived from the original on 2018-11-22. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

- ^ Levy, Clifford J. (June 7, 2010). "Estonia Raises Its Pencils to Erase Russian". Archived from the original on September 17, 2017 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Estonia". Amnesty International USA. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-30. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Levan Tvaltvadze (22 November 2013). "Министр культуры предлагает изучать русский алфавит в школе". Yle Uutiset. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

- ^ "Venäjän kielen opetuksen määrä romahtaa alakouluissa syksyllä". Yle Uutiset (in Finnish). 2023-02-28. Retrieved 2024-02-29.

- ^ "Муниципалитеты ходатайствуют об альтернативном русском языке в школе". Yle Uutiset. 31 March 2011. Archived from the original on 2016-06-02. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

- ^ Georgia. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ "Russian". Archived from the original on 2015-01-09. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- ^ "The Constitution of Abkhazia". UNPO. 2 November 2009. Archived from the original on 2018-11-15. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ "Конституция Республики Южная Осетия". Парламент Республики Южная Осетия (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2018-09-10. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ See Bernhard Brehmer: Sprechen Sie Qwelja? Formen und Folgen russisch-deutscher Zweisprachigkeit in Deutschland. In: Tanja Anstatt (ed.): Mehrsprachigkeit bei Kindern und Erwachsenen. Tübingen 2007, S. 163–185, here: 166 f., based on Migrationsbericht 2005 des Bundesamtes für Migration und Flüchtlinge. (PDF)

- ^ (in Latvian) Declaration of independence of 4 May 1990 Archived 5 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine (Retrieved on 24 December 2006)

- ^ "Statistics Portal". stat.gov.lv. Archived from the original on June 10, 2012.

- ^ Herszenhorn, David M. (February 19, 2012). "Latvians Reject Russian as Second Language". Archived from the original on March 6, 2017 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "Latvian president promulgates bill banning teaching in Russian at private universities". The Baltic Course. April 7, 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-08-11. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ^ "Government okays transition to Latvian as sole language at schools in 2019". Public Broadcasting of Latvia. January 23, 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-08-16. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ^ a b "Ethnic and Language Policy of the Republic of Lithuania: Basis and Practice, Jan Andrlík" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2016.

- ^ Pupkis, Aldonas (2023). "The Official Lithuanian Language in the Interwar Years". Vilnius University.

- ^ "Statistics Lithuania: 78.5% of Lithuanians speak at least one foreign language | News | Ministry of Foreign Affairs". Archived from the original on January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Employees fluent in three languages – it's the norm in Lithuania". Invest Lithuania. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ^ "Președintele CCM: Constituția nu conferă limbii ruse un statut deosebit de cel al altor limbi minoritare". Deschide.md. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Демоскоп Weekly. Об итогах Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года. Сообщение Росстата". Demoscope.ru. 2011-11-08. Archived from the original on 2014-10-18. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- ^ Об исполнении Российской Федерацией Рамочной конвенции о защите национальных меньшинств. Альтернативный доклад НПО. (Doc) (in Russian). MINELRES. p. 80. Archived from the original on 2009-03-25. Retrieved 2009-05-16.

- ^ "How many Russians are left in Dagestan, Chechnya and Ingushetia?". vestnikkavkaza.net. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017.

- ^ "22.07.2009 - Karelian language to be used for all national events". Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Goble, Paul (December 17, 2008). "Russification Efforts in Mari El Disturb Hungarians". Estonian World Review. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ The language question, the results of recent research in 2012 Archived 2015-07-09 at the Wayback Machine, RATING (25 May 2012)

- ^ Migration, Refugee Policy, and State Building in Postcommunist Europe Archived 2017-09-17 at the Wayback Machine by Oxana Shevel, Cambridge University Press, 2011,ISBN 0521764793

- ^ Ukraine's war of the words Archived 2016-08-17 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian (5 July 2012)

- ^ FROM STABILITY TO PROSPERITY Draft Campaign Program of the Party of Regions Archived December 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Party of Regions Official Information Portal (27 August 2012)

- ^ "Яценюк считает, что если Партия регионов победит, может возникнуть «второй Майдан»", Novosti Mira (Ukraine) Archived 2012-11-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Yanukovych signs language bill into law". 8 August 2012. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Constitutional Court declares unconstitutional language law of Kivalov-Kolesnichenko Archived 2018-06-27 at the Wayback Machine, Ukrinform (28 February 2018)

- ^ "Шосте загальнонаціональне опитування: мовне питання в Україні (19 березня 2022)".

- ^ "Соціологічне дослідження до Дня Незалежності: УЯВЛЕННЯ ПРО ПАТРІОТИЗМ ТА МАЙБУТНЄ УКРАЇНИ (16-20 серпня 2023)".

- ^ "Europeans and their Languages" (PDF). europa.eu. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-21.

- ^ "Ten Facts from Ireland's Census 2011". WorldIrish. 2012-03-29. Archived from the original on 2012-03-31. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ Στατιστική Υπηρεσία - Πληθυσμός και Κοινωνικές Συνθήκες - Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Ανακοινώσεις - Αποτελέσματα Απογραφής Πληθυσμού, 2011 (in Greek). Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 2013-05-07. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ "Ninilchik". languagehat.com. 2009-01-01. Archived from the original on 2014-01-07. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ "Language Use in the United States: 2007, census.gov" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-06-14. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ "Russian language returns to Cuba". russkiymir.ru.

External links

[edit]- Uralic family home page

- Language Controversy in Kyrgyzstan - Institute for War and Peace Reporting, 23 November 2005

- Ukrainian language - the third official? - Ukrayinska Pravda, 28 November 2005