Hooding

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: the article is full of POV information and claims. (November 2016) |

Hooding is the placing of a hood over the entire head of a prisoner.[1] Hooding is widely considered to be a form of torture; one legal scholar considers the hooding of prisoners to be a violation of international law, specifically the Third and Fourth Geneva Conventions, which demand that persons under custody or physical control of enemy forces be treated humanely. Hooding can be dangerous to a prisoner's health and safety.[2] It is considered to be an act of torture when its primary purpose is sensory deprivation during interrogation; it causes "disorientation, isolation, and dread."[3][4] According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, hooding is used to prevent a person from seeing, to disorient them, to make them anxious, to preserve their torturer's anonymity, and to prevent the person from breathing freely.

In 1997, the United Nations Committee Against Torture had concluded that hooding constituted torture, a position it reiterated in 2004 after the committee's special rapporteur had "received information on certain methods that have been condoned and used to secure information from suspected terrorists."[5]

Hooding is a common prelude to execution.[6][7]

Modern history

[edit]In the first half of the twentieth century, hooding was rarely used. During World War II, the Gestapo used it especially in the Breendonk prison in Belgium. It became more popular after World War II as a means of "stealthy torture," since it makes public testimony more difficult; the victim can testify only with difficulty as to who did what to them.[8] In the 1950s, hooding was used in South Africa[9] and French Algeria;[10] in the 1960s, in Brazil and Franco's Spain, in the 1970s, in Northern Ireland, Chile, Israel,[3] and Argentina; and since then in a great number of countries.[8]

In some cases, hooding was accompanied by white noise, such as in Northern Ireland;[11] such techniques used by British troops followed up on research done in Canada under the direction of Donald O. Hebb.[12]

Documented use of hooding

[edit]Argentina

[edit]After the 1989 attack on La Tablada Regiment, during the presidency of Raúl Alfonsín, the military reacted violently and again hooded prisoners; its methods were called "an immediate return to the methodology used during the dictatorship."[13]

Honduras

[edit]Battalion 3-16, the unit of the Honduran Army which carried out assassinations and tortured political opponents in the 1980s, was trained by interrogators from the CIA and from Argentina, and made up in part of graduates of the School of the Americas. Hooding was taught to Battalion 3-16 by Argentineans, who used a hood made of rubber called la capucha, which induced suffocation.[14]

Israel

[edit]In Israel, Shin Bet, the Israeli internal security service, uses hooding systematically (more systematically than the IDF), according to reports published by Human Rights Watch, who interviewed Palestinian detainees who had been hooded for extensive periods (four to five days at a time throughout their detention). They complained about hoods being dirty, having difficulty breathing, and suffering from headaches and pain in their eyes. The object, according to Human Rights Watch, wasn't so much the inability of victims to recognize their torturers, but to increase "psychological and physical pressure."[3] According to Amnesty International's influential report Torture in the Eighties, hooding and other forms of ill-treatment became widespread again after the resignation of Menachem Begin in 1984.[15]

Israeli troops are accused of using hooding in prisons in for instance Tulkarm (where 23-year-old Mustafa Barakat died while in custody, most of which he spent hooded[16]), Ashkelon (death of 17-year-old Samir Omar) and Gaza (death of Ayman Nassar); many deaths in Israeli detention centers involved hooded prisoners, such as Husniyeh Abdel Qader, who "was held in solitary confinement with her hands cuffed behind her back and her head in a dirty bag during the first four days of her detention."[17] In turn, Palestinian authorities in the West Bank were accused of the same practice in 1995, according to media reports and organizations such as B'Tselem.[18][19]

United Kingdom and Ireland

[edit]In the United Kingdom, hooding, one of the so-called "five techniques," was used as a means of interrogation during The Troubles, the period of violent conflict in Northern Ireland from 1966 to 1998, and notably so during Operation Demetrius.[20] In the prison Long Kesh, now known as Maze, prisoners were subjected to hooding in 1971: "throughout their days and nights of interrogation torture, their heads were kept covered by thick, coarse cloth bags."[21] Complaints quickly led the Heath government to order troops in 1971 "not to use hoods when interrogating prisoners."[22] On behalf of fourteen of these, the Republic of Ireland filed suit against the British government at the European Commission of Human Rights, which found in 1976 that the British had been guilty of torturing political dissidents. When, in March 1972, Direct rule was instated, the practice did not cease altogether, and at the end of 1972 the European Commission of Human Rights accepted a second case on behalf of victims of the practice.[21] In March 1972, the Parker report had concluded that the five techniques were in fact illegal under British law; on the same day the report was published, Prime Minister Edward Heath announced in the House of Commons that the techniques "will not be used in future as an aid to interrogation."[23]

While the practice was thus officially banned since 1972, reports of its use by British troops appeared during the Iraq War.[24] Hooding was discovered to have been applied in 2003 and 2004 to Iraqi prisoners who were held by American troops and questioned by intelligence officers from the British Secret Intelligence Service.[25] Baha Mousa, an Iraqi civilian, died in British custody after being hooded and beaten.[24]

United States

[edit]

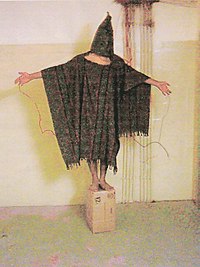

Most notably in recent history, hooding occurred at the Abu Ghraib prison[25] and at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp.[26] In 2003 already, Amnesty International had reported such abuse in a memorandum sent to Paul Bremer, then the head of the Coalition Provisional Authority.[27] Delegates of the International Committee of the Red Cross also protested the hooding of U.S. prisoners.[28]

In cases of extraordinary rendition by the United States, suspects are usually hooded, apparently as part of "standard operating procedures."[29] Sometimes, however, suspects are abused[30] and interrogated as well.[31] The famous photograph of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed taken not long after his capture, where he appears "dazed and glum," was taken moments after his hood was removed; he was hooded continuously throughout the first days after his arrest by commandos from the United States and Pakistan.[32]

Resistance to hooding is a standard element of the Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape training undergone by elite US military.[33]

Uruguay

[edit]According to a 1989 report by the Servicio Paz y Justicia Uruguay, hooding was the most common form of torture practiced in military and police centers in the 1970s.[34]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Amy Zalman. "Hooding". About.com. Archived from the original on March 23, 2010. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ^ Matthew Happold (April 11, 2003). "UK troops 'break law' by hooding Iraqi prisoners". Guardian News and Media Limited.

- ^ a b c Human Rights Watch/Middle East (1994). Torture and ill-treatment: Israel's interrogation of Palestinians from the Occupied Territories. Human Rights Watch. pp. 171–77. ISBN 978-1-56432-136-7.

- ^ Matthew Happold (April 11, 2003). "UK troops 'break law' by hooding Iraqi prisoners". Guardian News and Media.

- ^ "Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment" (PDF). United Nations General Assembly. 2004-09-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ J.A. Ulio (June 12, 1944). "Procedure for Military Executions". U.S. War Department.

- ^ Richard Ramsey (April 20, 2006). "Pierrepoint". Picturing Justice. Archived from the original on March 23, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ a b Rejali, Darius (2009). Torture and Democracy. Princeton UP. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-691-14333-0.

- ^ Millett, Kate (1995). The Politics of Cruelty: An Essay on the Literature of Political Imprisonment. Norton. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-393-31312-3.

- ^ Lazreg, Marnia (2008). Torture and the twilight of empire: from Algiers to Baghdad. Princeton UP. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-691-13135-1.

- ^ Streatfeild, Dominic (2007). Brainwash: the secret history of mind control. Macmillan. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-312-32572-5.

- ^ Streatfeild, Brainwash, 110.

- ^ Brysk, Alison (194). The politics of human rights in Argentina: protest, change, and democratization. Stanford UP. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-8047-2275-9.

- ^ Otterman, Michael (2007). American torture: from the Cold War to Abu Ghraib and beyond. Melbourne UP. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-522-85333-9.

- ^ Finkelstein, Norman G. (2008). Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History. U of California P. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-520-24989-9.

- ^ Ginbar, Juval (1992). The death of Mustafa Barakat in the interrogation wing of the Tulkarm Prison. B'tselem. pp. 8–9.

- ^ Rodley, Nigel (1994). "U.N. Commission on Human Rights, Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, U.N. Doc. E/CN.4/1994/31". Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- ^ "Torture, dark-of-night justice spread with Palestinian rule: Six security services kidnap, detain, abuse hundreds". The Washington Times. 1995-09-20.

- ^ "Furor Erupts over Reports of Torture by Palestinians; Investigator Catches Fire from Both Sides". Miami Herald. 1995-09-20. pp. 1A.

- ^ Streatfeild, Brainwash, 100.

- ^ a b Fields, Rona M. (1980). Northern Ireland: society under siege. Transaction. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-87855-806-3.

- ^ Jones, George; Michael Smith (2004-05-11). "Troops broke ban on hooding PoWs". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- ^ Lauterpacht, Elihu; C. J. Greenwood (1980). International Law Reports. Cambridge UP. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-521-46403-1.

- ^ a b Townsend, Mark (2004-12-19). "Ban on hooding of war captives: U-turn after outrage at treatment of Iraqi PoWs". The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ^ a b Johnston, Philip (2005-03-11). "MI6 officers broke law by interrogating hooded Iraqis". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ^ Sturcke, James (2006-03-06). "Guantánamo detainee tells of torture and beatings". The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ^ Simpson, John (2004-05-09). "Simpson on Sunday". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- ^ Caroline Moorehead (June 18, 2005). "Crisis of confidence". ICRC.

- ^ Drogin, Bob (2009-08-22). "Lebanese man is target of first rendition under Obama". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ Neville, Richard (2009). "The Fever That Swept The West". The Diplomat. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ Meldrum, Andrew (2006-06-13). "The vanishing point". The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ "In the first hours of his captivity the hood came off and a picture was taken....He appears dazed and glum." "Preparing a subject for interrogation means softening him up. Ideally, he has been pulled from his sleep — like Sheikh Mohammed — early in the morning, roughly handled, bound, hooded (a coarse, dirty, smelly sack serves the purpose perfectly), and kept waiting in discomfort, perhaps naked in a cold, wet room, forced to stand or to sit in an uncomfortable position." Bowden, Mark (October 2003). "The Dark Art of Interrogation". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ Benjamin, Mark (2008-06-18). "A Timeline to Bush Government Torture". Salon.com. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ^ Heinz, Wolfgang S.; Hugo Frühling (1999). Determinants of gross human rights violations by state and state-sponsored actors in Brazil, Uruguay, Chile, and Argentina, 1960-1990. Martinus Nijhoff. p. 288. ISBN 978-90-411-1202-6.